Recent Visit to the British Library

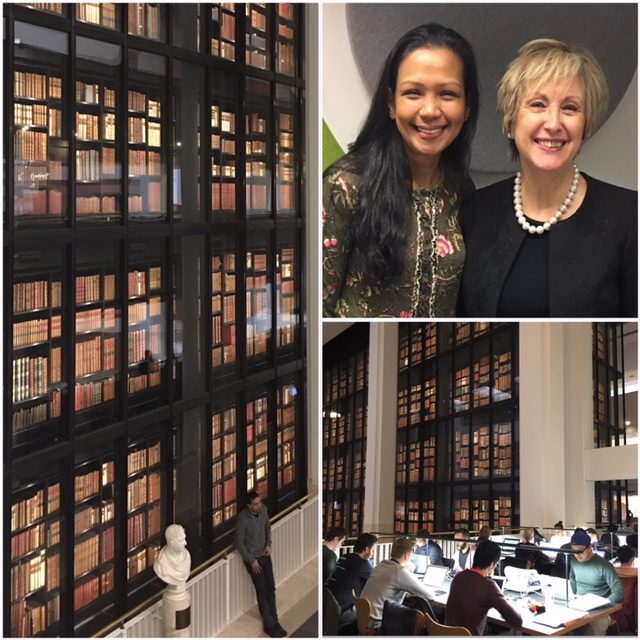

The British Library (BL) is one of my favourite places to hang out in London. I may sound eccentric to some people but hey, I make no apologies for having penchant for libraries and bookshops. 🙂 Since I moved to London, I’ve made numerous visit to the BL, mostly on my own, or sometimes with some visiting family and friends. I haven’t been there in a long time and last week I got to visit again. The highlight of the visit was meeting Patricia Lovett, a renowned English calligrapher and author (she was awarded the MBE ‘Member of the British Empire’ for services to heritage crafts and calligraphy). I have a copy of her recent book ‘The Art and History of Calligraphy’ and learned a lot from it. She happened to be conducting a workshop at the BL on Saturday, and she was very accommodating and sweet in showing me the work she was doing there. I am very much interested in attending one of her workshops soon, hopefully before the summer months.

After meeting Patricia, I visited some of the library’s most treasured objects — the ancient bibles and manuscripts. Now that I am learning English Roundhand (also known as Copperplate) script writing, I have been interested in studying the ancient writing. The British Library owns the only surviving complete copy of the Wycliffe Bible, and many other ancient bibles and manuscripts. I am always in awe every time I see them and wonder how long did it take to write one page of the Wycliffe Bible.

As a Christian and lover of history, I am grateful to the Lord for preserving His Word. I truly love the story of how we got the English Bible. It is one of the most fascinating stories I share with my visiting family and friends (that is, if they’re interested to know) when I take them to different locations in London that relate to Christian heritage.

It is indeed providential that the dramatic story of the English Bible started in England. When the theologian and Oxford professor/philosopher named John Wycliffe, first translated the Bible into English language in the 14th century, it caused a lot of uproar not just in England but all over the continent. At the time when only the Catholic clergy have access to the Bible, and only available in Latin (considered the language of the scholars while the aristocracy spoke French), Wycliffe’s translation was part of a Reformation campaign to make the Word of God and its teachings available to the general public. The Catholic Church opposed Wycliffe’s work, not only because it was a translation, but because it was a translation into English — the language of the common man. The Catholic Church was afraid that the people will finally discover ‘the truth’ for themselves. Wycliffe and his followers (they were called ‘Lollards’ – ‘fugitives’ in today’s language) had to painstakingly write the bible by hand as printing press wasn’t invented yet. Majority of these ‘Lollards’ were burned to death.

The English translation was banned, and, in 1409, it was made illegal for anyone to translate, read, or own the Bible outside of the clergy. Anyone caught reading or owning even just a page of the bible is burned to death along with the copy of the manuscript. Wycliffe was a good friend of the Prince of Wales who protected him so the Pope (Catholic Church) didn’t burn him at the stake, unlike most of his followers. He died of natural death in 1384, but the Pope ordered Wycliffe’s bones to be dug up 43 years after his death and burned not only as a posthumous punishment for his alleged heresy but also because the Catholics believed that the soul will not be resurrected if the remains of a dead person is burned.

The featured image and the following texts were taken from the British Library website; it’s not in any way comprehensive, but it’s quite interesting how the library summarised the story of the very first English Bible. Here it is:

Throughout medieval times the English church was governed from Rome by the Pope. All over the Christian world, church services were conducted in Latin. It was illegal to translate the Bible into local languages. John Wycliffe was an Oxford professor who believed that the teachings of the Bible were more important than the earthly clergy and the Pope. Wycliffe translated the Bible into English, as he believed that everyone should be able to understand it directly.

Wycliffe inspired the first complete English translation of the Bible, and the Lollards, who took his views in extreme forms, added to the Wycliffe Bible commentaries such as this one in Middle English (top left featured image). Made probably just before Henry IV issued the first orders for burnings to punish heretics in 1401, this manuscript escaped a similar fate.

Wycliffe was too well connected and lucky to have been executed for heresy, although the archbishop of Canterbury condemned him. The support of his Oxford colleagues and influential layman, as well as the anti-clerical leanings of King Richard II, who resisted ordering the burning of heretics, saved his life. Forty years after his death, the climate had changed, and his body was dug up, and along with his books, were burned and scattered. Nonetheless the English translations had a lasting influence on the language. ‘The beginning of the gospel of Ihesu Crist the sone of god,’ opens the Gospel of Mark, its first letter decorated with the Mark’s symbol, the lion. The commentary begins, ‘Gospel: the gospel is seid a good tellyng.’ Red underscores pick out the gospel text, while the commentary is written in slightly smaller script. The gold frame decorated with flowers and leaves and presentation of text and commentary are completely conventional for their time.

More than 1100 words are recorded for the first time in the Wycliffe Bible. Wycliffe is the earliest known writer to use the word ‘abominable’ to describe other people. It appears in these pages from the Book of Psalms, in the final column. The full phrase is: ‘þei ben corupt and maad abhominable in her wickednessis’ (they are corrupt and made abominable in their wickednesses).

I must add this, in the words of Dr. Ken Connolly (he made a series of videos on the ‘History of the English Bible’): Wycliffe’s bones were dug up 43 years after his death; his ashes were scattered on the River Avon; Avon flows into River Severn; Severn into the narrow seas; and eventually into the ocean. And that’s exactly what happened with the Word of God. From England, it reached the new world, America, and eventually into the rest of the world. I’ll blog, hopefully soon, about the other treasures of the British Library.

Featured Image: British Library. Wycliffe Bible, handwritten either by John Wycliffe himself, or any of his followers, c1400. Photography at the ‘most treasured ancient scripts’ of the British Library is strictly prohibited, but they have digitised some of the ancient manuscripts to make them available to the public.