Things I learned about the British Culture: Christmas Traditions (Part 2)

In this series: ‘Things I learned about the British Culture’ Part 1.

Before I moved to London I knew next to nothing about the Christmas traditions in the UK. I had no idea that the main Christmas meal is eaten at lunchtime or early afternoon on Christmas Day; that the dinner table is decorated with Christmas Cracker; that people eat goose, brussel sprouts, pudding and mince pies for dessert (I thought mince pies were made with mince beef!), that they drink mulled wine, and that they tell their kids that their presents were from Santa. Seriously, every kid in the Philippines knew that Santa is a fake. Houses have no chimneys so how was he supposed to climb down to deliver the presents? Besides, it’s hard to believe that Santa is real when you see a skinny Filipino guy at the shopping malls or a hotel lobby dressed up in a red suit with fake cotton beard. 😆

In the last five years I’ve been reading up on British social history especially on the Victorian and Georgian era, and I’ve learned a lot about the culture including of course, how the British people celebrate Christmas. From my readings, I came to realise that no era in British history has influenced the way in which people around the world celebrate Christmas quite as much as the Victorians. Before the young Queen Victoria reigned in 1837 nobody in Great Britain had heard of Santa Claus or Christmas Crackers. Neither had anyone ever sent a Christmas card, nor had a day off from work on Christmas day. The industrial revolution of the Victorian age brought technology and wealth that changed the face of Christmas forever not just in this country but around the world. I wanted to highlight some of the Christmas traditions we practice today — thanks to the influence of the Victorians. 🙂

Christmas Family Gathering and Gift-Giving. The prolific English writer Charles Dickens wrote books like Christmas Carol, published in 1843, which encouraged wealthy Victorians to give money and other form of gifts to the poor. With the rise of the middle class families as a result of the Industrial Revolution, these ideals eventually spread to all levels of the British society. Dickens’ most famous story is credited to have had the greatest impact on Christmas celebrations not just in the west but the rest of the world. The story focused on the triumph of good over evil, the sharing of material blessings, and the importance of family, and it brought a completely new meaning to Christmas in the Victorian era and established the modern interpretation of Christmas not just as a festive family gathering but also as a time of charity — of giving money and other gifts to the poor.

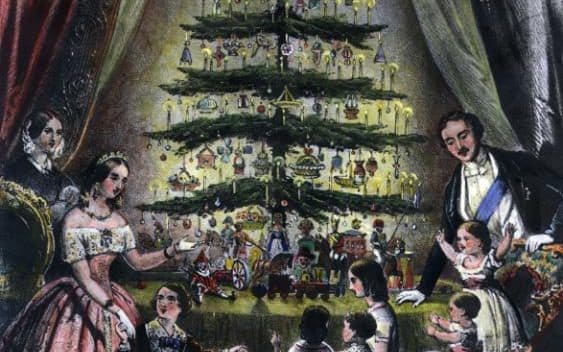

The Christmas Tree. The Christmas tree was not widely used in Britain until the mid 19th century. The book “Christmas-tide, Its History, Festivities and Carols, With Their Music” by William Sandys (first published in 1852) tells the story of how the Christmas tree became popular in Great Britain following the marriage of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria. When Victoria married Albert in 1840, the German prince brought with him to the marriage his love of the Christmas tree, which had not been a custom in England at that time, and he made the Christmas tree as popular in Britain as they where in his native Germany. Albert and Victoria were first cousins, (Victoria’s mother was Victoria Maria Louisa of Saxe-Coburg, sister of King Leopold of the Belgians), and Victoria grew up very familiar with the custom of her family. The ornaments and lighting up of the Christmas tree was a distinctive feature of Victoria’s childhood Christmases not only because it was a tradition of her descendants back in Germany but it had been introduced to the family by her grandmother, Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III. For Christmas Eve 1832, the 13-year-old Princess Victoria wrote in her journal: “After dinner we then went into the drawing-room near the dining-room. There were two large round tables on which were placed two trees hung with lights and sugar ornaments. All the presents being placed round the trees…” The tree Victoria was referring to was the Christmas tree that had been placed at Kensington Palace where she was born and lived until she inherited the crown. The tree that Prince Albert brought to Windsor Castle in 1841 was decorated with the finest hand blown glass ornaments from Germany with candles and a variety of sweets, fruits and gingerbread. In 1847, Prince Albert wrote: “I must now seek in the children an echo of what Ernest (his brother) and I were in the old time, of what we felt and thought; and their delight in the Christmas-trees is not less than ours used to be.” Prince Albert also presented large numbers of trees to schools and Army barracks around the country during Christmas season, and he would decorate those trees himself with gingerbread, candies, dolls, strings of raisins, almonds and other nuts, and candles which were lit on Christmas Eve for the distribution of presents, and relit on Christmas Day, after which the tree was then moved to another room until Twelfth Night (January 6). Traditionally, gifts were laid out on linen-covered tables beside the tree.

Around this time, the Christmas tree became popular in other parts of Europe, and by 1871, the influence of the Royal Christmas Tree and Dickens’ Christmas Carol had brought Christmas into full bloom.

The Christmas Holiday. As a result of the industrial revolution during the Victorian age, the middle class families had the money to take time off work on December 25th and 26th, Christmas Day and St Stephen’s Day. December 26th was considered ‘servants and working people’s special day’ — a time designated for the working class to open their gifts given by their employers and other wealthy people. The railway also enabled many people who work in the city to travel back home to spend Christmas with their loved ones. Today majority of British people do relax on Boxing Day but some people get out and take part in sporting events such as football matches and horse racing while others go shopping and take advantage of the best bargain. Traditionally, the Boxing Day match is also a very popular event in the sporting calendar. In 1871, St Stephens Day (Boxing Day in England — December 26th to the rest of the world) was included in the Bank Holiday Act.

Santa Claus. Also known as Father Christmas, Santa Claus is always associated with ‘charity’ or the giver and distributor of gifts. However, the two are in fact two entirely separate stories. Father Christmas was originally part of an old English midwinter festival, dressed in green which is a sign of the return of the spring season. The stories of St. Nicholas or Santa Claus came via Dutch settlers to the ‘New World’ (what we now call America or the USA) in the 17th Century. From the 1870s, ‘Sinter Klass’ (to the Dutch) became known in Britain as ‘Santa Claus’ and with him came the ‘make-believe’ story of a fat old man with long beard traveling across the world in his reindeer and sleigh to distribute gifts to the children — dropping gifts off through the chimney.

The Christmas Stocking and Children’s Gifts. At the start of Queen Victoria’s reign, children’s toys were handmade and therefore quite expensive, and only wealthy people could buy them. With the advent of factories however, came mass production which brought with it games, dolls, books, and toys at a more affordable price. In a poor child’s Christmas stocking, which first became popular in 1870s, only a handful of fruits such as apple, orange, berries, and a few nuts could be found. Today just about every family with little children in the UK have Christmas stockings filled with goodies hanging by the fireplace or somewhere in the living room.

The Christmas Cards. The first three years of Queen Victoria’s reign, sending Christmas cards wasn’t even a part of the Christmas tradition in this country. There was a so-called ‘Penny Post’ that was first introduced in Britain in 1840 by Rowland Hill — the idea was simple, a penny stamp paid for the postage of a letter or card to anywhere in Britain. This simple idea paved the way for the sending of the first Christmas cards. Sir Henry Cole in 1843 tried to print a thousand cards for sale in his art shop in London at one shilling each, and it became a big hit. The popularity of sending cards became more popular when in 1870 a half-penny postage rate was introduced as a result of the efficiencies brought about by the new transport system — the railways. Today some people still send Christmas cards through the post according to Royal Mail but for majority of the British people, an ecard is sent rather than a paper card.

Turkey for Christmas Dinner. Today many English people serve goose, turkey, ham and/or beef with all the trimmings for Christmas dinner. A number of food historians claim that turkeys had been brought to Britain from America hundreds of years before the Victorian age. When Queen Victoria first came to the throne however, both chicken and turkey were too costly for most people to enjoy. Roast beef was the traditional fare in northern England for Christmas dinner while in London and the south of England, goose was favourite. Many poor people made do with rabbit. The Christmas Day menu for Queen Victoria and family in 1840 included both beef and of course, a royal roast swan. By the end of the century most people feasted on turkey for their Christmas dinner.

The Christmas Crackers. Invented in 1846 by a London candy maker, Tom Smith, the Christmas cracker is now a huge part of the Christmas dinner table throughout the country. The original idea was to wrap his sweets in a twist of fancy coloured paper, but this developed and sold much better when he added love notes, paper hats, small toys and made them go off ‘bang’ once the cracker is pulled. In the UK many families pull Christmas crackers at the dinner table at lunch time on December 25th. The humble cracker is a Christmas table essential, and add the perfect final touch to the table setting. One is set at each dinner plate. Each cracker contains a paper crown, which is compulsory to wear at the table and there will be a lot of cajoling or joking to get a grumpy Grandad or a fussy Granny to wear his or her crown. Usually there will also be a joke to read out usually a pun on words — essentially, the joke has to be very corny to make everyone sigh and/or retire to the couch and fall asleep. 🙂 All the shops around the country do sell a selection of crackers — fun, foodie, chic, and many other different themes imaginable to make the festive season goes off with a bang. When the cracker is pulled it activates a firecracker that makes a loud ‘crack’ and whoever gets the longest end, gets the prize. Prizes can vary from cheap plastic toys, charms to gold pins depending on how much you can afford.

Christmas Carols. A lot of the traditional Christmas carols that we sing today originated during the Victorian times. The Victorians loved music — thanks to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert who both were very musical, and as part of their holiday celebrations, began to revive old medieval English carols. Many Victorian musicians composed new ones, both secular and religious, most of which are of course, written in English — all time favourites as It Came Upon a Midnight Clear, Good Christian Men Rejoice, O Little Town of Bethlehem, Away in a Manger, O Come all ye Faithful and We Three Kings reflected the religious side of Christmas while cheerful songs like Jingle Bells celebrated the joyous side of the holiday season. All of these classic Christmas songs were written and popularised by the Victorians. Singing was a very popular form of home entertainment since the Victorians had no radio or television. Everyone is encouraged to participate regardless of their singing ability and they composed easily sung music that celebrated the cheer of Christmas. Some musicians assembled old and new nativity carols into collections such as ‘Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern’ in 1871, Handel’s ‘Messiah’ and strains of ‘O Holy Night’ that filled not just the homes but the churches as well. The tradition of caroling from door to door originated with the singers and musicians ‘The Waits’ who visited houses singing and playing the new popular carols. They would sing carols outdoors on the front porches of houses in England and the custom later became popular in the United States in the late 19th century and continued on to this day not just in the west but around the world.

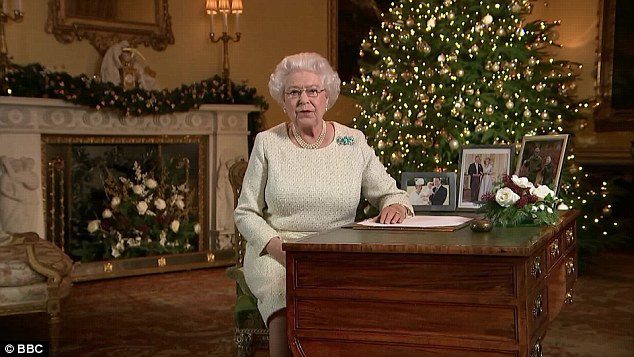

Last but not the least, The Queen’s Christmas Message. At 3pm on Christmas Day each year, the majority of British people would sit in front of their television and switch on to BBC One to listen to The Queen’s Christmas Message. There will be clips of the Royal Family to highlight the major events of what they accomplished throughout the year; and the Queen will deliver a speech on what the Nation will focus on in the coming year. The focal point of her speech varies; a reflection on the past 12 months, and it could be an emphasis on social issues such as the elderly, veterans, unity of faiths, etc. However, the speech is not something that The Queen’s Private Secretary wrote, she really has no voice on the matter but simply a ‘deliverer’ of the message from Number 10 Downing Street. The speech is commissioned by the Prime Minister for the Government of the day, and The Queen simply reads it to the nation. The British people watch The Queen intensely to see her facial expressions; they interpret every gestures if there is any hint of approval or disapproval in her manner while delivering the words. The Christmas broadcast dates back to 1932, the idea of Sir John (later became Lord Reith), to plug his Empire Service, now the BBC World Service. King George V, not initially enthusiastic about the idea, was persuaded during a tour of the BBC, and broadcast from a makeshift studio at Sandringham, hooked up by telephone lines to Broadcasting House, for the next three years, though he complained it ruined his Christmas Day. His final broadcast was delivered a month before his death in January 1936. King George’s successor, Edward VIII, who made a radio broadcast in December 1936, although it was on the 11th rather than the 25th, and announced his abdication rather than seasonal glad tidings. Since 1959, when she was heavily pregnant with Andrew, The Queen broadcasts have been recorded a few days before Christmas, though the content remain secret until it’s aired on Christmas day.

The programme ends with a rousing anthem of God Save The Queen and there will be people standing up and raising their glasses. According to a survey conducted a few years ago, some very traditional British families only partake their Christmas dinner after The Queen had delivered her speech while some will be crashed out, and snoring on the sofa by the time she concluded the message. For those of us in the minority, myself included, who are not glued in front of the tv to watch Her Majesty’s speech but prefer to watch the replay later on in the day, her words are taken with a grain of salt.

I’ll leave you with a beautiful rendition of ‘O Holy Night’ by Kings College Choir. It is my mother’s favourite Christmas song, and I never get tired of listening to this. It’s one of the Christmas songs that will never get old to me.

For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace. (Isaiah 9:6, King James Version)

I wish you all a Happy Christmas and a blessed new year.

(Featured Image: Trafalgar Square, Guide London)